Summer, 2004.

It was unbearably hot, we were unbearably cranky, so my mom loaded us all up in Big Brown and away we trundled to our Aunt Nancy’s house. She, my uncle, and my cousins lived in Toledo’s Old West End — a delightful trip back in time. On the way to their house, you pass the hotel where Al Capone stayed when he was in town on…business. You drive down Collingwood Avenue — a narrow street lined with tall, tall trees that used to be the central promenade of this Victorian neighborhood. The interwoven branches high above you created a tunnel that vaulted you back in time.

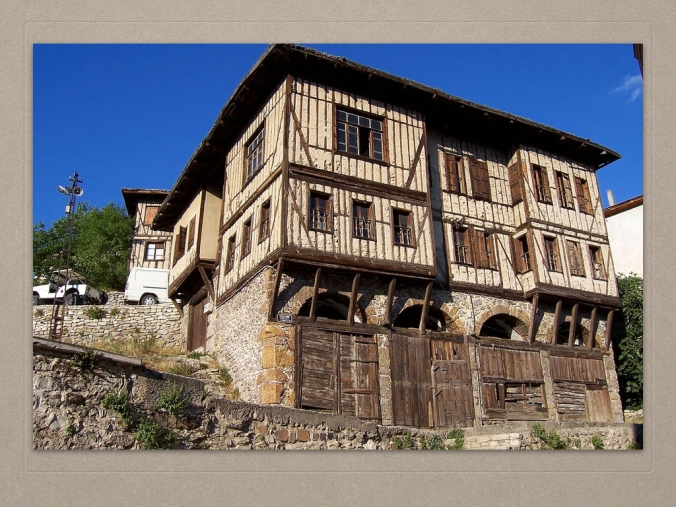

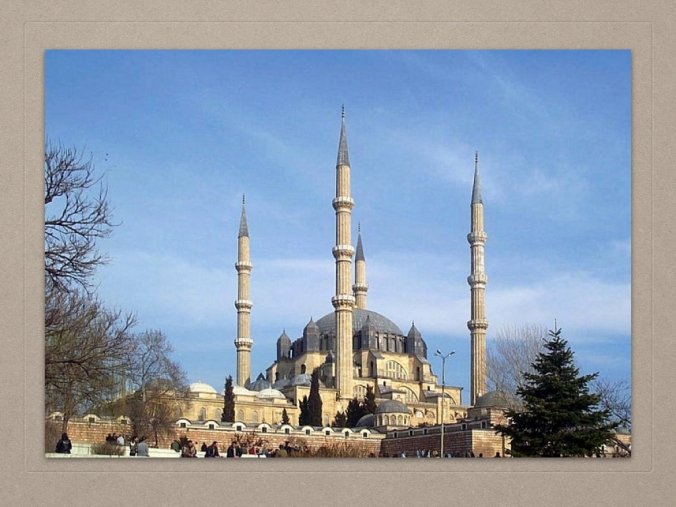

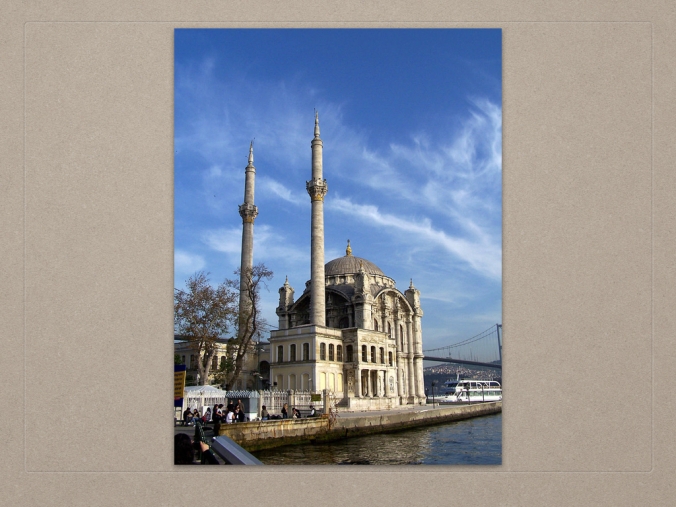

Collingwood is, oddly enough, covered in churches. The Greek columns of a Christian church abut the more staid facade of a Seventh-Day Adventist temple. My cousins lived on a street that boasted a modest one church that presided across the street and three lots down. The battered houses there had the same draw for me as ancient ruins — equal parts crumbling and stately, but still beautiful.

As a kid, I couldn’t quite comprehend this particular neighborhood. On one side, there was the rough neighborhood around Bancroft street with its huddled houses and huddled people. On the other side, through the tunnel of Collingwood, was downtown Toledo with its hard-edged skyscrapers, solemn public offices, and sprawling baseball stadium. In between sat the Old West End.

As a kid, I couldn’t quite comprehend this particular house. My Aunt Nancy’s was a classic Victorian with indigo paint and a wide, sturdy front porch. During the winter, when night fell on the snow that smoothed over the modern edges of the neighborhood and electric candles graced the windows, you would almost expect to hear the clack of hooves as a sleigh rounded the corner bearing a fur-swaddled and be-muffed family ready for bed. The house came equipped with the two standard staircases — grand and servants’. It still retained the segregated calling rooms — a ladies’ parlor and a gentlemen’s smoking room. There was even a two-story stable in the back that had been converted into a two-car garage. The unfinished basement showed signs of the original root cellar. My cousins told me that a house down the street had a ballroom where the attic should have been.

I had to process a lot of dissonance caused by what I saw, and in more ways than one. One the one hand, this was nothing like what I was used to. Where this house had darkly glistening wood floors and high plaster ceilings, my house had carpet and ceilings low enough that, when thrown, a bouncy ball would ricochet back and forth between floor and ceiling upwards of five times. On the other hand, the clash of modern and historic made for an interesting tableau. An exquisite stained glass rose embellished one ground floor window while on the adjacent sill squatted an air conditioner unit.

However, that air conditioning unit was like a single ice cube in a cup of tea. We were boiling. So we made the trip 20 minutes across town and a hundred years back in time to that house on Parkwood because it had the holiest of middle-class grails next door: the above-ground pool. Oh yes. Today was not the day for making a slip-n-slide out of a tarp weighted down by bricks in the corners (woe be him who did not mindeth the cinderblocks). Today was the day for luxuriating in all 52 sweet inches of cool, refreshing, chlorinated-as-all-hell water. Because it was deeply summer and exponentially hot, there was not way we were getting out of that water until we were falling asleep in our floaties and wrinkled as prunes.

We dove for rings. We made a whirlpool. We had splash fights. We played King of the Raft. We played Marco Polo. We played Guess That Tune — but underwater. We jumped, dove, belly-flopped in and rated the performances one to ten like it was the olympics. Somewhere in there, my cousin Tom decided to show off his best “matrix moves.” This involved falling backwards into the water whilst pinwheeling the arms in slow motion. One by one, we all tumbled slowly back into the water. Even me. Even though I had no idea who or what “matrix.” was.

E.D. Hirsch would be ashamed of me.

The Matrix is, of course, a 1999 blockbuster sci-fi film known for its slow-motion action sequences and the iconic scene image of Keanu Reaves’s Neo bending impossibly backward in order to avoid a spray of bullets. It had certainly made its mark not only in the cinematic realm but in the cultural realm to the point where even a kid who had never seen the movie knew that it involved slow-mo stunts. Thus, it would certainly be included on an expanded/updated edition of Hirsch’s original list of Things the Culturally Literate Know.

However, part of me still balks at the idea of a culture being quantifiable. It seems so like Hirsch is creating some sort of wizard formula that goes something like: apple pie + George Washington + The Louisiana Purchase + Elvis + the moon landing = America. Or rather, knowing about apple pie, George Washington, The Louisiana Purchase, and the moon landing makes you an American. My gut instinct is that culture should not be so easily definable, but on the other hand, how else do we describe it? When you talk about going to visit a foreign country to get a taste of the foreign culture, you mean sampling their food, art, architecture, geography, and architecture. In the same way that apple pie + George Washington + The Louisiana Purchase + Elvis + the moon landing = America, haggis + sheep + bag pipes + Edinburgh Castle + William Wallace + Nessie = Scotland. Again, I am torn between the notion of recognizing these things that are undoubtedly Scottish and saying that they define what Scotland is. It just seems too presumptuous to reduce an entire country/culture/people to a meager list.

And this list is only growing. If it helps, let’s put it in the modern terminology of data. Back in the Victorian era, the average person did not generate that much data. If they were literate, they probably wrote a few letters or kept a small journal, but that was probably it. If they had their picture taken or sat for a portrait, it definitely did not happen that often — maybe only twice in their lifetime. Now think about modern times. One college student could produce as much writing in one semester for one class as another person produced in their entire life. One college student could take eight selfies in one trip to the bathroom instead of having to sit eight weeks for a portrait. There is so. much. data.

I’m not sure Hirsch saw the internet coming.

How can one possibly be expected to observe, process, and store so much information?

In his New York Times opinion piece, Karl Taro Greenfield describes the cultural literacy version of faking it. Faking Cultural Literacy is Greenfield describing this exact problem. He talks about scrolling through Facebook but never clicking on any of the shared links, discussing a scientist’s paper even though he’s never read the paper, and forming opinions on books he’s never read. He discusses that even though you don’t necessarily care about the trending tags on twitter, you’re expected to not only know about them but have an opinion about them. As Greenfield puts it, to know all is almost impossible and to somehow not know all is to fall out of touch:

The information is everywhere, a constant feed in our hands, in our pockets, on our desktops, our cars, even in the cloud. The data stream can’t be shut off. It pours into our lives a rising tide of words, facts, jokes, GIFs, gossip and commentary that threatens to drown us.

For me, this sort of faking it is most expressed in the realm of geekiness. Like NHL aficionado-hopefuls might bluster their way through a conversation with a hardcore puckhead by mumbling about Gretzky, Lemieux, and Crosby — and how much the Oilers are struggling — I can talk to diehard Whovians with a certain amount of confidence about weeping angels and fish fingers with custard even though I’ve only seen exactly one episode of Doctor Who. The same goes for Supernatural fans (I just mumble something about Destiel), Attack on Titan fans (just hum the theme song), and Big Hero 6 fans (gush about how cute Baymax is and you’ll be fine) even though I’ve only seen fractions of each source material. I call this phenomena “nerd osmosis” — where you just kind of absorb the information of the general group around you, because there is no way you could possibly know every single fandom that is represented on Tumblr or at Comic-Con.

So to E.D. Hirsch I would say: I don’t think Cultural Literacy exists. At least, not in the way he pictured it. I don’t know if the idea of being culturally literate has changed or the culture to which we are literate has changed, but there seems to exist a disconnect nevertheless.

Part of this is just me playing devil’s advocate. Because, as my friends joke, being a Reamer means communicating almost exclusively in M*A*S*H, Psych, School of Rock, and Disney movie quotes — with a good bit of misappropriated song lyrics thrown in. So how do I reconcile the part of me that instinctively rejects E.D. Hirsch’s assertions on the basis that they seem pretentious with the part of me that can recognize references to Romeo and Juliet and connect the suffix in Gaza-gate to the original Watergate scandal?

I would offer an amendment to E.D. Hirsch and tell him that the loss of culture is natural. Victorians, who produced a very finite amount of information and had a very finite idea of what an education or educated person looked like, would have a much easier time of mastering the culture. Nowadays, the idea of cultured person is much harder to define because the culture is harder to define and quantify. This is the information age but there is only so much information a person can reasonably be expected to remember. And each new generation has it worse than the one before because they have even more details to deal with. The globalization of culture via the internet and the increasing ease of international culture also further blends the idea of American culture with other cultures. As Greenfield puts it:

So here we are, desperately paddling, making observations about pop culture memes, because to admit that we’ve fallen behind, that we don’t know what anyone is talking about, that we have nothing to say about each passing blip on the screen, is to be dead.